Paradise Club in Mykonos by night.

While sailing from one Greek island to another in pursuit of authentic Greek life, a traveller can easily locate the stunning architecture, pristine beaches and charming cliff-top communities that attract countless tourists every year.

Yet finding examples of the massive economic crisis plaguing one of the world’s most popular vacation destinations is a somewhat more elusive task.

I discovered as much during my recent 10-day romp around Greece.

From Mykonos, where the winding streets are still crammed with cash-flush fashionistas eager to shop and squeeze into the many nightclubs, to quiet, picturesque Syros, where tourism is not the primary source of income, and Santorini, the glamorous and still bustling mecca for the international jet set, life hardly appears to be coming to any sort of standstill in Greece.

At least not on the islands, far removed from the political turmoil in Athens.

For months, Greece’s financial crisis has been the stuff of international headlines, with protests, bank closures and a potential Grexit all part of the ongoing spectacle as the nation struggles to address its enormous debt and develop some sort of bailout agreement with the European Commission (EC), the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and the European Central Bank (ECB).

Viewing the drama from afar has left many people with an uncertain opinion of the country.

Tell someone you’re visiting Greece these days and the responses range from “Stay safe!” to “Bring lots of cash with you”. Some even question your sanity when you admit your plans.

But the reality on the ground in this popular tourist destination is a far cry from the turmoil projected in news reports. At least at first glance.

There are no lines outside banks or in front of ATMs in Athens, or anywhere in the country for that matter. Most stores, restaurants and other businesses are operating normally. And the Greek people, while expressing exhaustion and frustration with the economic uncertainty of life, are doing their best to help each other get by until better days arrive.

“If you’re just sitting at home watching the news overseas, you think the whole country is falling apart, but that’s not the case at all,” says Nicholas Filippidis, director of product development in North America for Celestyal Cruises, a company that specialises in providing an authentic Greek experience by offering voyages to off-the-beaten-path destinations throughout the country.

Far from falling apart, or coming to a standstill, the country and its people are perhaps working overtime to maintain some semblance of normalcy, while also preserving Greece’s largest industry: tourism.

TOURISM IS GREECE’S LARGEST INDUSTRY

There are indeed cracks in this façade, but they show up in ways that tourists on vacation, busily shuttling between the Parthenon and the islands, are not likely to notice. The evidence can be seen in the all-too-quiet shipyards where workers, no longer being paid, have stopped showing up. Or in the struggle of average Greeks to make ends meet amid strict banking limitations. Some locals will tell you that those who are able to, particularly the younger generations, have left the country in search of opportunity elsewhere, such as Germany, the US and Canada.

But even amid such upheaval and frustrations, the outward demeanour of most Greeks continues to be optimistic, upbeat and hard at work catering to tourists still flocking to the country.

On Mykonos, the streets, cafes, restaurants and nightclubs are all jammed with twenty- and thirtysomethings happily preening before their selfie sticks. The Armani and Bulgari shops are doing business all day and night. And at sunset, there’s not a seat to be had anywhere in the island’s picturesque, waterfront Little Venice neighbourhood. As evening descends, the music of nightclubs takes over the party island and the festivities continue until early morning.

Antonis Pothitos, a licensed tour guide on Mykonos, says many people are now visiting as a show of support for the country, while others, not at all put off by the economic issues, have maintained previously scheduled vacation plans.

But there are some impacts even here. Many of Pothitos’ countrymen, unable to find employment in whatever career they trained for, are now competing for work in Greece’s most reliable business – tourism.

“Everybody wants to do the same job I’m doing, but they’re not qualified and have no licence,” he says with obvious frustration, urging tourists to make sure that, when hiring a guide, they possess a valid licence.

SYROS, GREECE

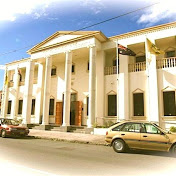

On the island of Syros, one of the smallest islands in the Cyclades, life also seems remarkably undisturbed – but in a much different way to Mykonos. Here tourists can wander the streets of the elegant Vaporia district in Ermoupoli, admiring historic, colourful mansions of ship owners, practically alone. It is almost eerily quiet, a great find amid the country’s busy tourist season.

Syros is a rare example of an island where tourism is not the number one industry. That’s because during the 19th century, the island grew to be the commercial, naval and cultural centre of Greece, and while that dominance has faded, Syros is still home to many shipyards and textile manufacturers.

“The major problem caused by the economic crisis is there are fewer jobs,” says Daniela Winkler, a longtime resident of the island. “But Syros is less impacted, because people here own a lot of land, they can go fishing, families have two or three incomes, so there is always one person with a job. And many families share a car amongst two or three people, so they make ends meet and don’t feel the crisis as much.”

Most of the tourists who visit Syros are Greek, meaning the island has seen a drop in its tourist revenues.

source:Neos Kosmos